The beauty of knowing nothing

There is no place where I am more acutely aware of my beginner’s mind than in an art gallery. I enter, hoping for an experience and I’m seldom disappointed. I am clear that I know nothing, and I’m only walking through on my reactions and responses, and I try to simply honour that. To that end, I collect the catalogs but don’t look at them until after I’ve been with the art. This is perhaps not how they are meant to be used, and I do understand that I’d have a different experience if I learned something first, but I like my method. Writing it out here makes it sound planful, but honestly, I just go into the gallery or museum waiting for something to pluck my emotional strings.

That’s how I went to Mass MOCA early this month and I left with heartstrings humming. I’ve been wanting to tell you about it, but it is hard! Making words around experience, especially visceral body experience, is limiting. As a writer, my work is about finding and shaping words, but it isn’t easy.

The map vs the landscape

I’ve written elsewhere about the difference between having an experience and then putting words around it. The experience shrinks to accommodate the description, but using words is the only way we can share some part of the experience with other people, and connecting with others is critical to our well-being. We tolerate the flattening of our remembered experience to share it. To make a connection.

I’ve been conflicted between not wanting my MOCA experience to shrink into description and my desire to share it. I think I’m ready. Finally.

The museum visit feels, in hindsight, like a pilgrimage, though I only intended to pass some time before my next stop. It’s a pilgrimage in a sense because it took me somewhere I didn’t even know I needed to go. I’m still processing much of it.

The experience

I have a New Englander’s affinity for those old brick factory buildings from the late 1800s, ubiquitous in river towns of Maine and New Brunswick. The Industrial Revolution hit hard, changing almost everything from a local, agrarian, seasonal world to a global one marked by business interests and the invention of the time clock. A few years ago, I went to the Lowell, Massachusetts, National Historical Park* where the decades of shift from an agricultural to an industrial society is remembered and preserved. That’s probably another whole essay, but for today’s purposes, I’ll just note that the repurposing of those old factories has been a renaissance of sorts. In my current hometown, the cotton mill has become government offices. In North Adams, Massachusetts, the mills are now the Museum of Contemporary Art. Mass MOCA, originally conceptualized in 1986.

The space itself evoked the generations of workers, the noise of the machinery, the devastation of mill towns when manufacturing left, ghosts wandering through the coffee shop, wide-open lobby, sunlit spaces. The buildings, 26 buildings of the complex, hummed with purpose. **

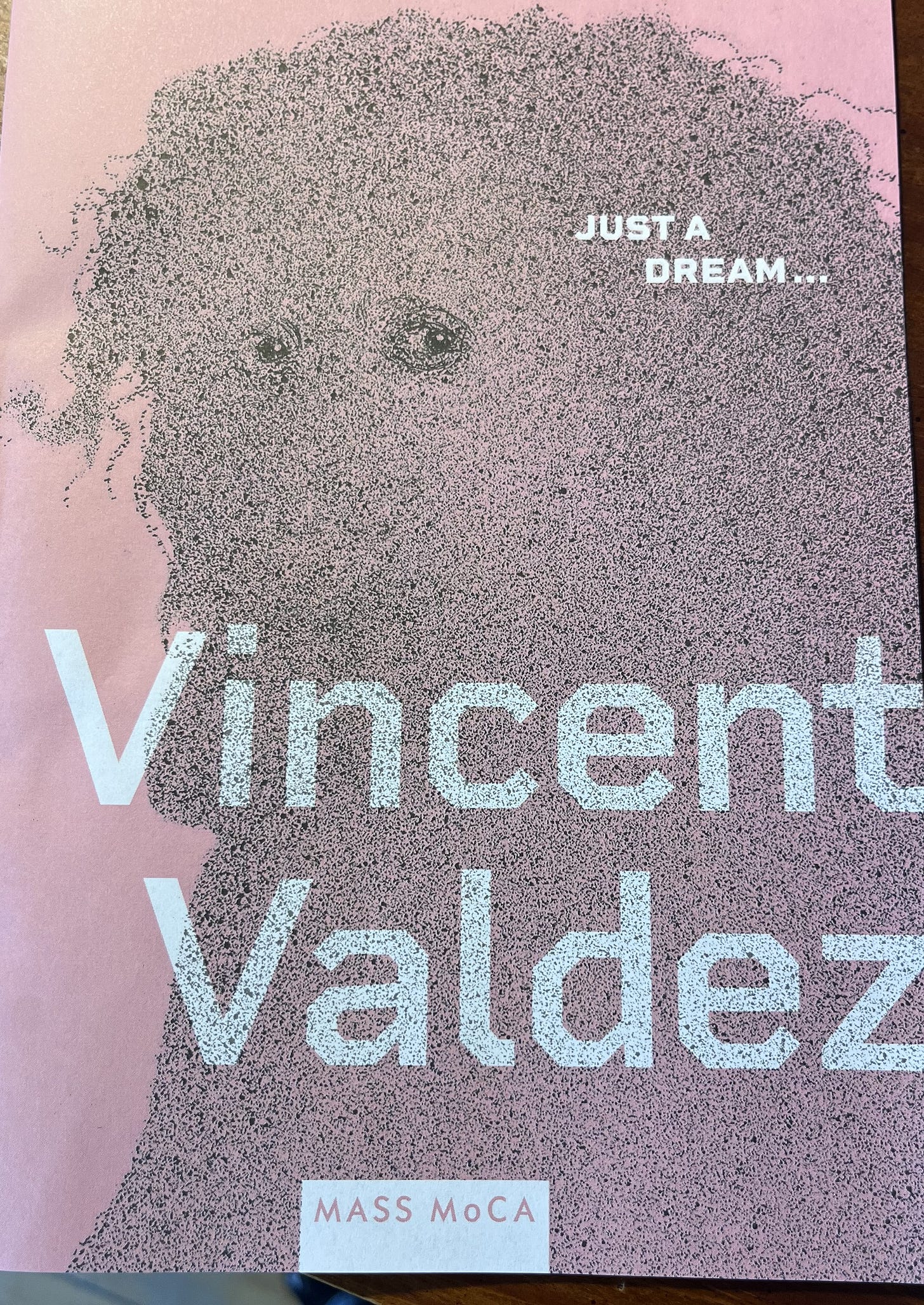

A ticket, a map, and a list of recommendations got me started. With a single glance, unseen forces pulled me into the first-floor gallery housing Vincent Valdez: Just A Dream.

From the lobby, the massive work of life-size Klansmen, backgrounded by a nighttime city, piles of trash, lit by the headlights of a pickup truck, both repelled and compelled me. I followed the compulsion, noting my unease, disturbance in my belly. I threw in a mantra for protection (‘Art can’t hurt you.’) and approached the wall where the hooded figures gazed directly into my eyes.

Valdez is quoted in the catalog. “I think it is safe to say that my work resonates like an alarm that rings nonstop in my head.”

Not only in his head; my alarm shrieked at full volume. The group included men, women and a baby in Nikes, an iPhone, a Rolexed wrist, be-sheeted and hooded, holding objects, each other and a baby. This the first image in a series he calls “The Beginning is Near (An American Trilogy).”

More impacts to the viscera: a series of portraits of the speakers eulogizing Muhammed Ali, an incredibly diverse group of people who all spoke of the humanitarian work of Ali. I had no memory or experience of the event, but the images still spoke.

In another room Ollie North, larger than life, held up his hand to declare he was speaking the truth. In my mind… “Liar, liar, liar!” ***

I around the room. I needed somebody to share this with. A woman about my age was also there, absorbing the image.

“I remember this, do you?”

“Oh, yes,” she said. “I certainly do.”

That was enough for me, and maybe too much for her, but I was grateful for the contact. Reminded me of our essential natures, the need to connect with others when we feel something.

There was more, of course. In The Strangest Fruit, Valdez composed paintings of contemporary Latinos hanging as if from trees, hands and feet bound, heads drooping. The catalog refers to the postures as simultaneously reflecting the lynching of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans along the Texas border, a hundred years ago, and ascension (though no image of ascension found in my search included bound figures). Gazing at the images brought me grief, but later reading the context, it was layered with horror.

There’s an entire series on boxing, Latino boxing, and a gorgeous commentary on a neighbourhood in Los Angeles from the 1960s. The artist’s sketches that accompanied the only illustrated version of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five are part of the display.

Stickiness (in a good way)

I’ve been incubating this experience for weeks. Now it’s showing up explicitly in my conversation and even my google searches.

The Valdez show was the point of entry for me into MOCA, and it stuck. Parts of it have stuck in a deep way. Talking about it, thinking, digging into the history that the artist has shoved at me, saying, “Here. Look. This happened.”

This confrontation, I suspect, is the purpose of art. It travels far beyond intellectual curiosity.

The Valdez work is unflinching. It made me look with different eyes. There is no artifice here. I felt the work as a blow to the body and psyche, an awakening of sorts. Or a reminder of an ongoing awakening. Familiar. Shock, horror, and beneath that, grief.

I grieve for my lost country, but of course the country remains. What is lost is the idealized version of the US that I grew up with, sanitized and heavily scented with white saviourism, but for all those limitations, a powerful image of something good standing up against evil.

I mark the cold water of shock hitting me in 2004 when the atrocities being committed in the name of “good” at Abu Ghraib became public, and suddenly a lot of history fell into place. The good parent turned out to be an abuser, and I’ve been struggling with that ever since.

Credit to therapy

Years of therapy allowed me to go into the museum with an open mind and open heart. Letting myself feel whatever I feel, well, that’s an advanced skill for me. In my thirties, I could readily tamp down any emotion, and I had a particular distaste for sentimentality, the disparaging label I put on things that might move me. I was so afraid of my own feelings I could not allow myself to have them.

This policy came out of a safety protocol learned in childhood. Don’t draw attention! Don’t ever be angry, but also, don’t be too happy, either. The sad but true thing is when you shut down emotion, it all gets shut down.

Years of therapy, especially bioenergetic therapy, helped me become less guarded. If I couldn’t feel anything, I’d have no reason to visit Mass MOCA, except perhaps as a “should.” Therapy also helped me stop “shoulding” on myself.****

More to come?

I have much more to tell you about that visit, including a book (imagine! Me with a book!) I collected while there. But that’s for another day.

Thanks for reading. Where have your heartstrings vibrated lately? Comment to get the conversation going.

Footnotes of a sort

*https://www.nps.gov/lowe/index.htm

** https://massmoca.org/about/history/

*** The whole Iran-Contra Affair was in 1986, a year I was busy with a new baby and his siblings plus graduate school. I was certainly aware of the goings-on, but in a remote, not-directly-affected way. Things look different in hindsight, of course.

**** A bit of a therapy joke. If you say it out loud, it sounds like you’re saying a different word. Notice when your internal monitor tells you that you ‘should’ do or think or feel something. Then check in to see who is telling you that? Can you drop that rule?